A Screening for visual Impairment among pupils in primary schools in Mbalmayo

Keywords:

visual impairment, School children, school eye healthAbstract

Background: Mbalmayo town is located 50 km away from Yaoundé, the capital city of Cameroon. It has 37 public schools and 12 private schools, with over 17,278 pupils. School eye health programme is a public health priority in Cameroon

with weaknesses in its policies including, a lack of national protocol for visual impairment (VI) screening, few specialists engaged in the process, no effective reference centres for the screened, and no school eye health rapid assessment (SEHRA) data available. This led us to determine the prevalence of visual impairment among primary school pupils in Mbalmayo.

Methods: It was a cross-sectional study, conducted between December 2021 and June 2022, in 12 purposively selected primary schools within Mbalmayo that were located less than 5 km from Mbalmayo District hospital and were easily accessible by car. The visual acuity (VA) of pupils in class 1 through class 6 was tested using the E Snellen chart. The vision testing was conducted by 4 teams of 3 persons each. The teams consisted of second-year student ophthalmic nurses and third-year student opticians. Visual impairment was set at VA < 6/9 in at least one eye, with or without any optical

correction. Parents of those with visual impairment (VI) were invited by a phone call or a letter to bring their children for an ophthalmic examination at the Mbalmayo District Hospital.

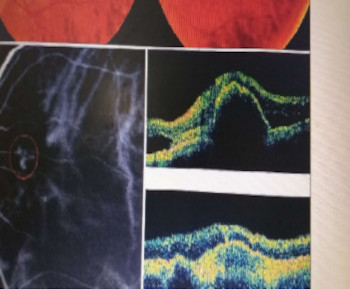

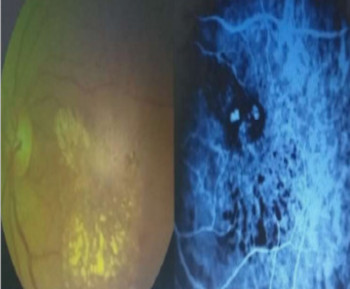

Results: A total of 9061 pupils aged between 5 and 15 years under went VA testing. There was a female predominance of 51.4%. 364 pupils were visually impaired, giving a prevalence of 4 %. Of these, 153 pupils presented at the hospital, that is 42.2 % of those requiring ophthalmic assessment. Of those who showed up, 21.6 % had no VI (i.e.false positives). Ocular disorders found included: refractive errors (77.1%), allergic conjunctivitis (5.2%), strabismus (3.3%), suspected glaucoma (3.3%), oculocutaneous albinism (3.3%) and cataract (1.3%). Refractive errors included astigmatism (56%), hypermetropia (35%), and myopia (9%). The summed-up prevalences for all types of myopias (myopic astigmatism and spherical myopia) revealed aprevalence of 37.5% (Table 1).

Discussion: The prevalence of VI in this study is less than those from other African studies done in Ethiopia1, Nigeria2 and Tanzania3 which were 5.2%, 6.9% and 10.2%, respectively. This discrepancy could be explained by different cutoff points for VI.A low proportion of pupils showed up for the hospital phase of the investigation. This is best explained by our weak referral system, as opposed to the smartphone-based screening technique4, which could greatly enhance hospital referrals. We also found the need for more training of the screeners in order to reduce false positive rate. Because they were students in their final year of training, it was expected that they knew how to measure visual acuity, so we didn’t perform a training session. In our next screening, we should train them and get a good level of agreement of

teams to standardizeour procedures. All forms of astigmatism were the major form in the varied ametropia noted, as opposed to hospital-based findings in Cameroon that reveal spherical hypermetropia instead5. Myopias were highly prevalent, consistent with worldwide trends and is probably explained by excessive near-work or screen time of our pupils6.

Conclusion: Vision impairment among pupils in Mbalmayo is prevalent at 4%. Refractive disorders were the main aetiologies for vision impairment.

References

Gashaw G. W., Mohammed D. B., Teshome G. G., and Birhan A. A. Visual impairment and associated factors

among primary school children in Gurage Zone, Southern Ethiopia. Afr Health Sci. 2020 Mar; 20(1): 533–542.

Megbelayin E. O. Prevalence of amblyopia among secondary schoolstudents in Calabar, south-south Nigeria. Niger J Med. 2012 OctDec;21(4):407-411.

Wedner SH, Ross DA, Balira R, Kaji L, Foster A. Prevalence of eye diseases in primary school children in a rural area of Tanzania. Br J Ophthalmol. 2000 Nov; 84(11): 1291–1297.

Hillary K Rono, Andrew Bastawrous, David Macleod, Emmanuel Wanjala, GianLucaDiTanna, Helen A Weiss, Matthew J Burton. Smartphone-based screening for visual impairment in Kenyan school children: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet Glob Health. 2018 Oct; 6(10): e1072.

Ebana Mvogo C, Bella-Hiag A L, Ellong A, Metogo Mbarga B, Litumbe N C. Les amétropiesstatiques du noir

camerounais (The static ametropia of black’s Cameroonian). Ophthalmologica. 2001 May-Jun;215(3):212-216.

Morgan IG, Ohno-Matsui K and Saw SM. Myopia. Lancet 2012;379: 1739–1748

Downloads

Published

How to Cite

Issue

Section

Categories

License

Copyright (c) 2023 Transactions of the Ophthalmological Society of Nigeria

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.